SET was a game I used to play with my family years ago, and I was reintroduced to it recently while attending the Recurse Center. I was looking for an excuse to play with OpenCV, and teaching a computer to play SET seemed like a good choice.

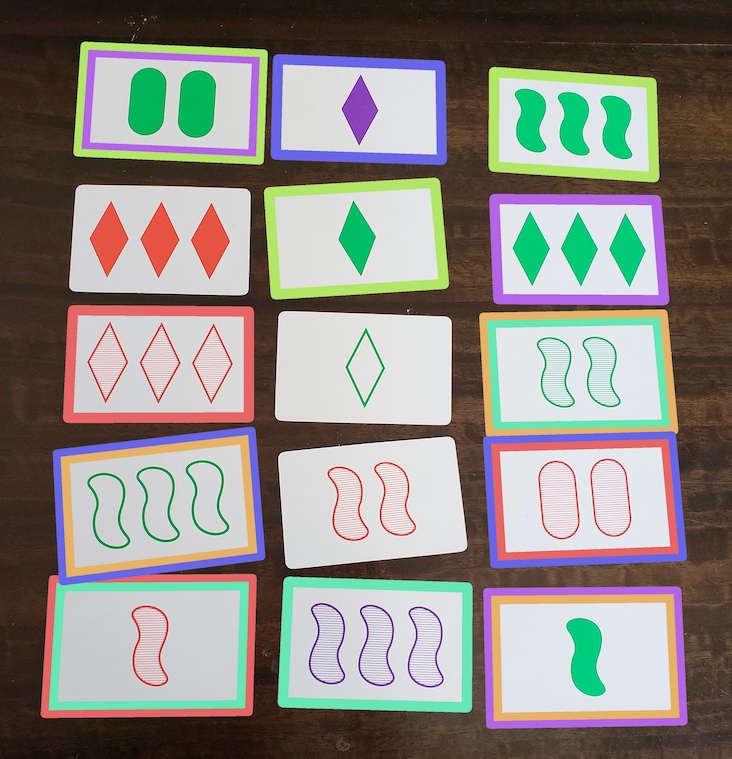

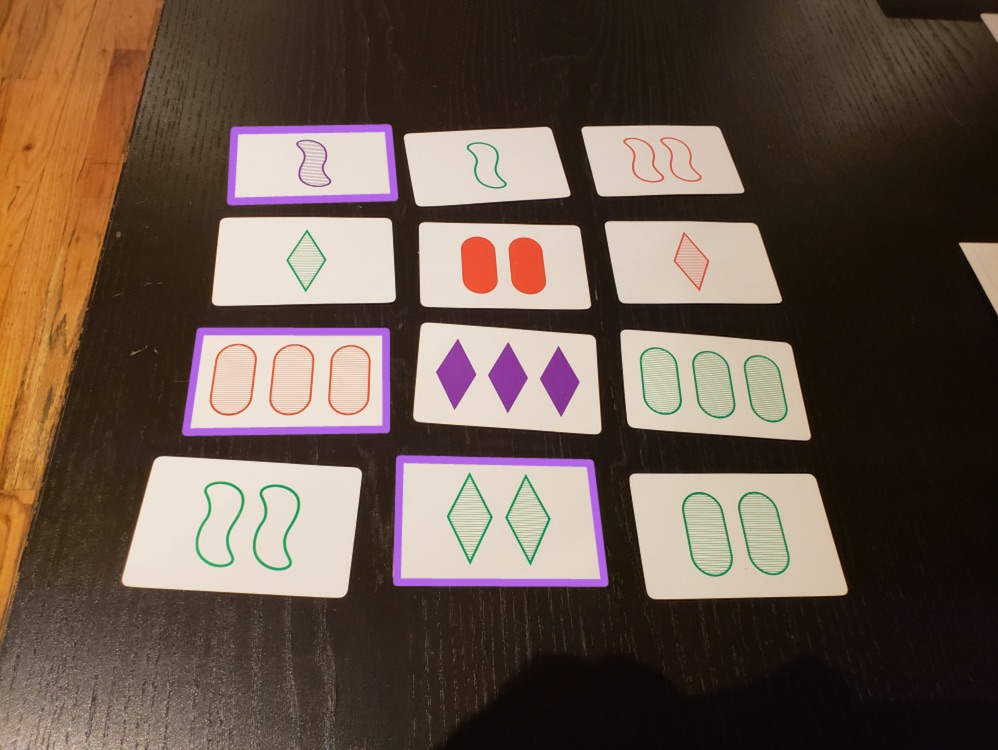

A quick primer on SET: each card has four attributes: shape, color, number, and fill, each of which can have three different values. There are 34 combinations, and so a deck of SET cards has 81 total. A set is three cards that, for each of these attributes, are either all the same, or all different. There’s usually going to be 12, sometimes 15, and very rarely 18 cards out at any given time. Whoever can identify a set the fastest wins it, and whoever has the most sets by the time the entire deck is dealt has won the game.

Extracting cards from the image

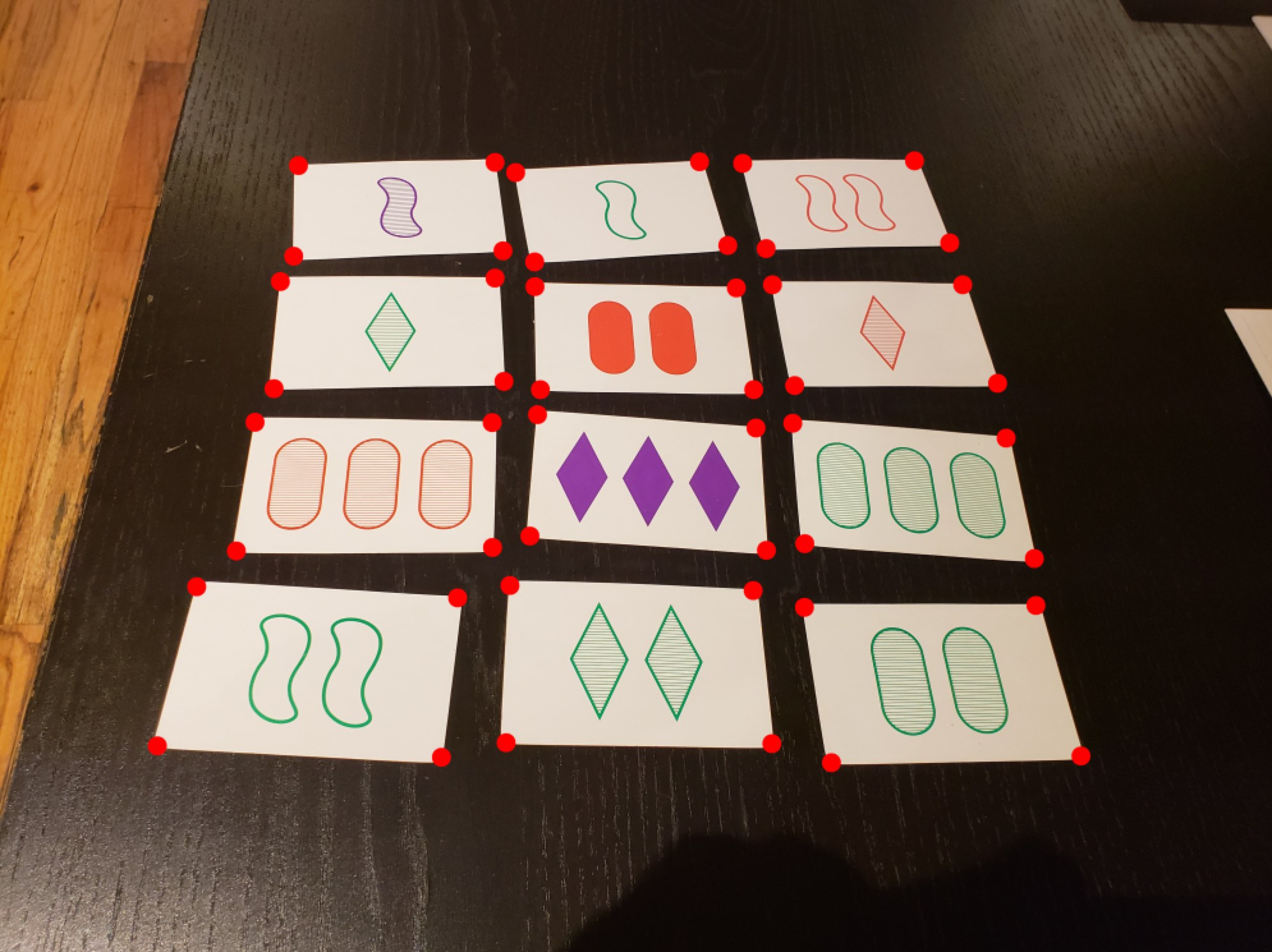

I decided the first step to this would be to identify each card in an image. Luckily, Arnab Nandi had already solved that problem. So, my “game image -> individual cards” piece of the pipeline is more or less the same as his, with a few modifications.

Nandi’s method involves taking the largest shapes from the image and assuming they’re cards. Set is played on a table which may have other objects on it, so we need to do a bit more work. Aside from ignoring all polygons that are not quadrangles, we can also ignore polygons with areas that vary greatly from the median of the largest 15. Assuming there isn’t a huge amount of clutter on the game table, the photo is taken from too far away, or there is a large amount of perspective warp (admittedly, a lot of caveats), the median of the 15 largest objects in the photo is likely to be a card. So, if any of the objects are vastly larger or smaller than this median area value, it’s likely not a card. This method filters other rectangular objects, such as the SET card box, and the symbols on the cards themselves, which sometimes are classified by cv2.findContours() as quadrangles.

Nandi’s method also assumes orientation of cards - I want my implementation to be a little more flexible, so I have a function which attempts to put all cards in landscape position, by rotating the quadrangle if the height is greater than the width. This again fails if there’s too much perspective warp, or if the photo is skewed in relation to the grid of cards, but it works well otherwise.

With these methods, my limited testing showed that if you’re careful about the lighting and angle, the program will reliably extract the individual cards from the image.

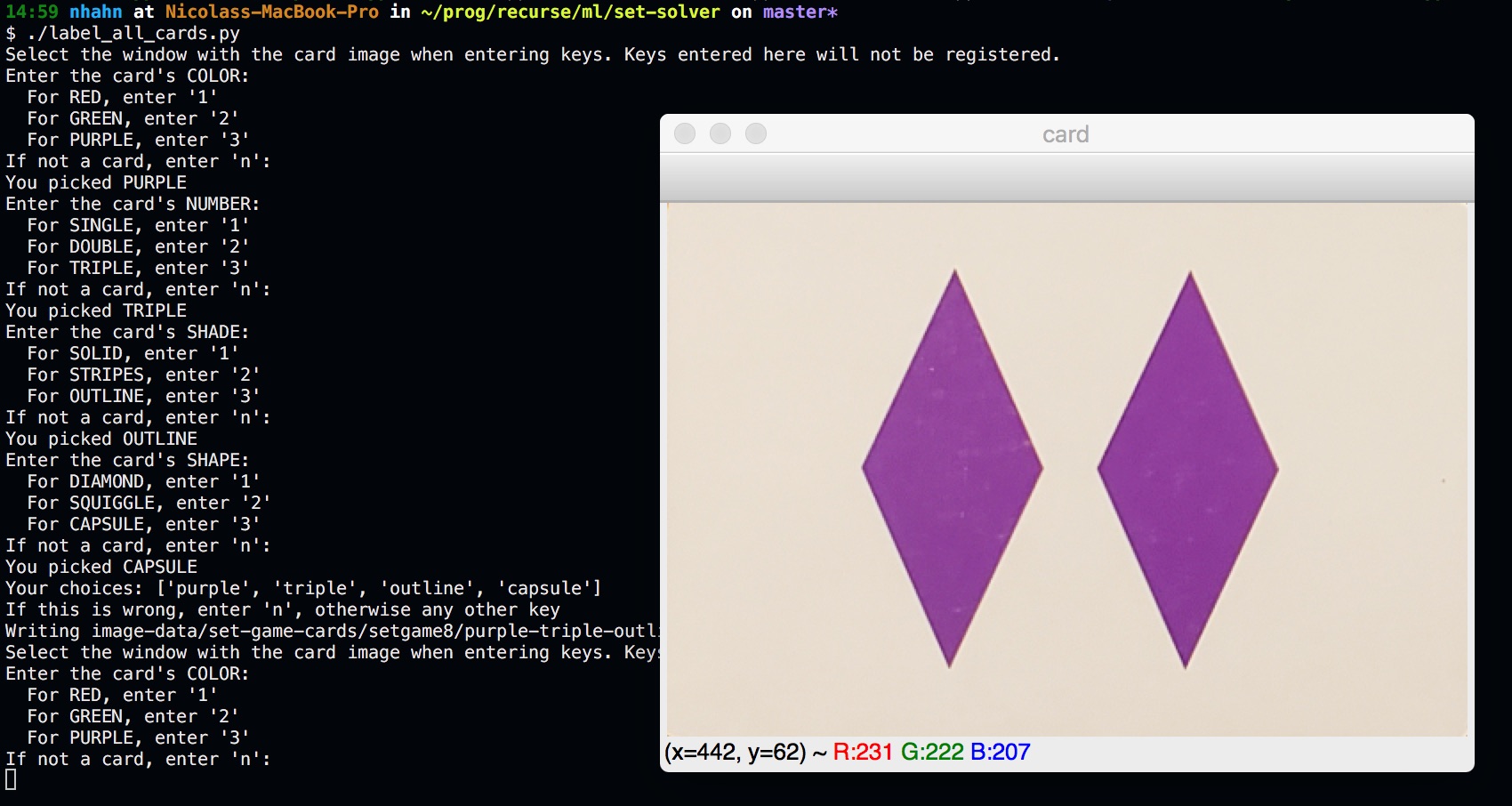

Classifying cards

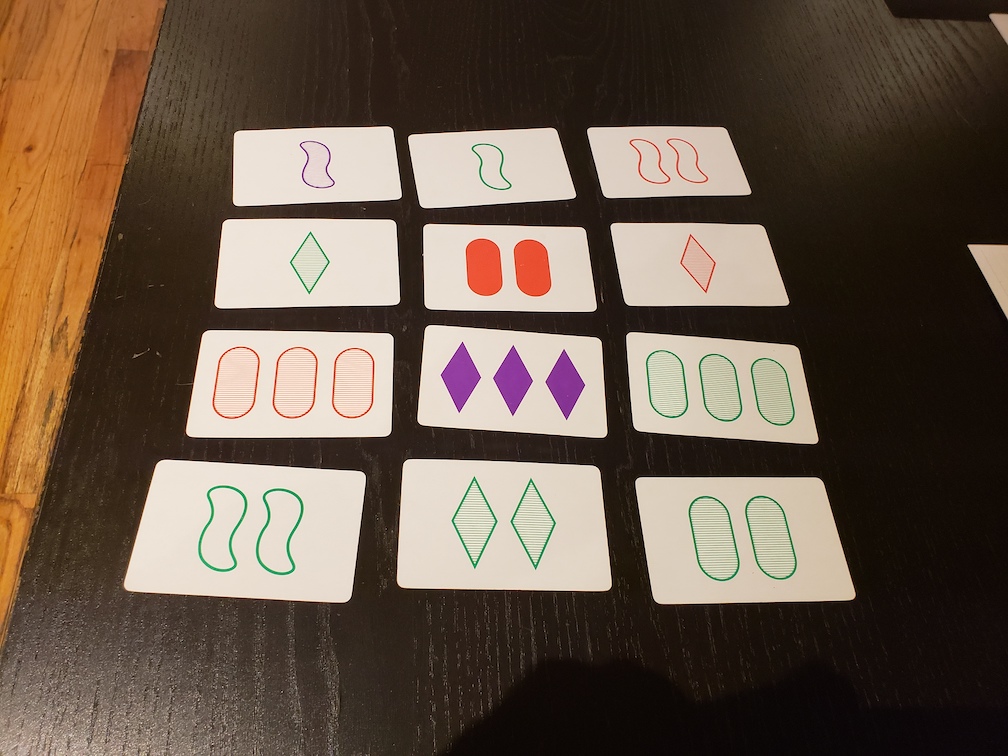

In order to solve the image, we’re going to need to know what cards are in it. I decided the first thing to do is to make a labeled dataset of all the cards in the deck. I wrote a script to speed up the process of manually labeling cards. I laid all the cards out on a table, photographed them, and fed them to the script, which would use the method above to cut out the card images. It would then show me a card and prompt me to enter ‘1’, ‘2’, or ‘3’ for each attribute to indicate which category, and save the card with a filename that contains these attribute categories.

We now have individual images of all the cards in the deck, labeled. Great! Now, we need to classify the attributes of an unknown card. I prefer to use the simplest method that works, so let’s try something easy: differentiate each card in a SET game against every image in our deck dataset. I used a small python library I wrote called diffimg, which quantifies the difference in two images of the same size by comparing the RGB channel values for pixels at the same coordinates.

As it turns out, this only sort of works: it can often get the correct shape and number, but not the shade and color. It often confuses red and purple, as well as striped and outlined shapes. As it turns out, when you do a per-pixel comparison, things like the lighting of the image and slight positional misalignment overwhelm the shape/color/shade/fill match.

Looks like we’ll have to be a bit more sophisticated. I decided I would try to classify each attribute separately, and assemble the results to get the final card classification.

Color

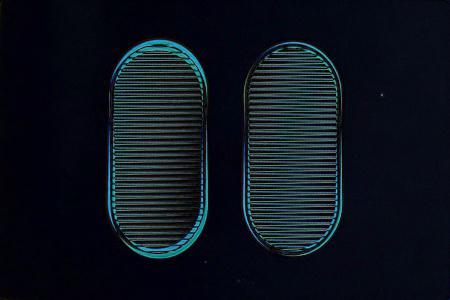

An idea I had for this was to distill the average color of a card’s shape(s) into one RGB value, and compare it against the averages of labeled cards. A friend showed me an article on Noteshrink with code for doing exactly that. Broadly, the way it works is: given a number of colors n, reduce the bit depth of each pixel’s color information until all the pixel’s color values fit in n buckets. Doing so pushes hues that are close to each other in 3-dimensional RGB space towards a single value. So for example, using this image:

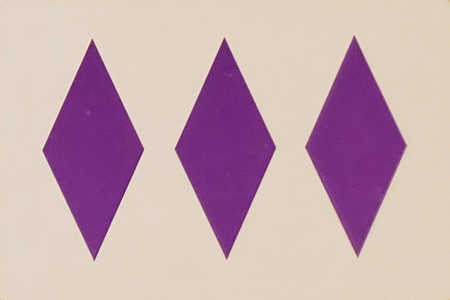

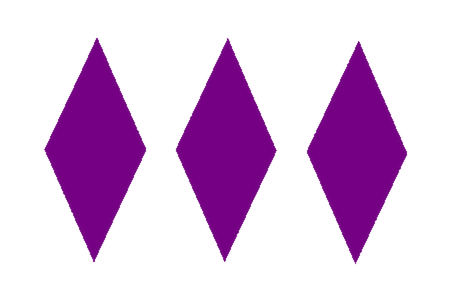

We set n = 2 to condense all the different purple hues into one value:

Once we have this image that has been reduced to a single color on a while background, we can take the RGB value of that single color and compare it to the averages of each of the red, green, and purple labeled cards (after they’ve been through the same bucketing process). This is precomputed to speed up classification. Simply finding the minimum RGB distance is enough to get an accurate color classification.

Number

Classifying the number of the card works very similarly to the card extraction process. We again use cv2.findContours() to find the contours in the image, and count how many are over a certain minimum area value (to avoid things like reflections, stains, or specks of dust on the card).

Shape & Fill

The shape and fill classifiers use OpenCV’s ORB, a feature detection algorithm. A feature is basically what the algorithm thinks is an “interesting” part of an image, oftentimes a corner/curve of a shape, or an isolated point, but there is no hard definition of what features can be. They are also repeatable - the algorithm needs to be able to use features to find the same object in different images.

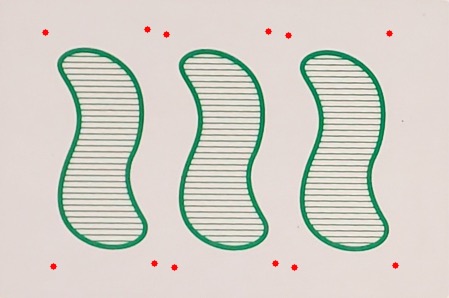

The classifiers start with a cutout of one of the shapes of the card that was found during the number classification step, and the top few features (the ones that ORB thinks are the most important) are compared to the top few features of each of the possible labeled shape+fill combinations. The labeled shape with the most matches is used for the fill classification for the card.

The shape classification is identical, save for one step: an edge detection filter cv2.Canny() is applied to the shape image before ORB is applied. This was added as a result of trial and error, but my intuition is that Canny() cuts down a lot of detail in the image that’s useful for fill detection, but is just noise when looking at shape.

Now all four attributes of the card have been classified, and so we know what cards we have on the table. Now we can find all the sets.

Finding the Sets

This turns out to be the simplest part of the system! The logic for solving SET after all cards have been classified is just:

- Generate all combinations of three cards.

- Discard the combos where any of the attributes (color, number, shape, fill) have exactly two unique values (for example: the card number attributes are

[1, 1, 3]). The SET rules page calls this the “Magic Rule”: If two are… and one is not, then it is not a set.

def is_set(cards):

for attr in cards[0].attrs.keys():

if len(set([card.attrs[attr] for card in cards])) == 2:

return False

return True

def find_sets(cards):

combos = itertools.combinations(cards, 3)

sets = [c for c in combos if is_set(c)]

return sets

Generating all 3-card combinations results in O(n3) runtime complexity. Not ideal, but since there’s never going to be more than 15 cards in an image, this works. There is a way to do it in O(n2) - can you figure out how?

Knowing which cards belong to what set, we can draw colored boxes around the cards to indicate which are sets. The results:

And we’re done!

Where to go from here

You can view the project source on Github.

I’ve thought about two methods of extending the project. My original plan was to have it run on a phone as an AR app - this would probably require a rewrite in something other than python, as well as optimizations so that it can update in real time (it takes about 5 seconds to generate the above image on my mid-2015 15” Macbook Pro).

Another idea that was presented to me: play against the computer using a projector and webcam mounted on the ceiling pointing at a table (which the Recurse Center has). The projector could display just the colored borders around cards on the table. Difficulty could be set by how long the computer would wait before showing a set.

Special thanks to my friend Okay for encouragement, guidance, and contribution!